This is a lyrical, fiercely smart book, written with a healthy dollop of dry humour. Anthropologist Lochlann Jain scrutinises cancer as a social phenomenon, detailing its contradictions, hypocrisies, representations and devastations, all with an insider’s wry knowledge. Woven into the eloquent discussions of medical malpractice suits, cancer statistics, and how one can actually measure ‘quality of life’ are casual mentions of Lochlann Jain’s own brutal foray into the cancer industrial complex, which included an attempt to sue their doctor for misdiagnosis.

“This book unpacks the head-spinning ricochet that characterises a cancer ‘journey’. It revolves around the stamps put into my passport by the immigration officials at the gates of the kingdom of the ill.”

Chapters explore the thorny issue of cancer screening; the likelihood of hormone treatment for IVF and menopause contributing to cancer; and the detritus we accumulate over the course of treatment in order to fashion as ‘normal’ a life as possible. Here, Lochlann Jain critiques the ‘Look Good Feel Better’ programme, with its drive to normativity and the contradiction of cosmetic brands giving thousands of dollars’ worth of make-up to programme, while also resisting research into the carcinogenic effects of its products. I shared their ambivalence about this programme – I did go to a LGFB workshop, but the ‘goodie bag’ I left with remains almost completely unused, and it’s been many years since I wore make-up. Similarly, I was always reluctant to wear wigs or prostheses. But as Lochlann Jain points out, social lives depend on cultural norms, and, with or without cancer, many people spend their whole lives striving to ‘pass’, maintaining these norms.

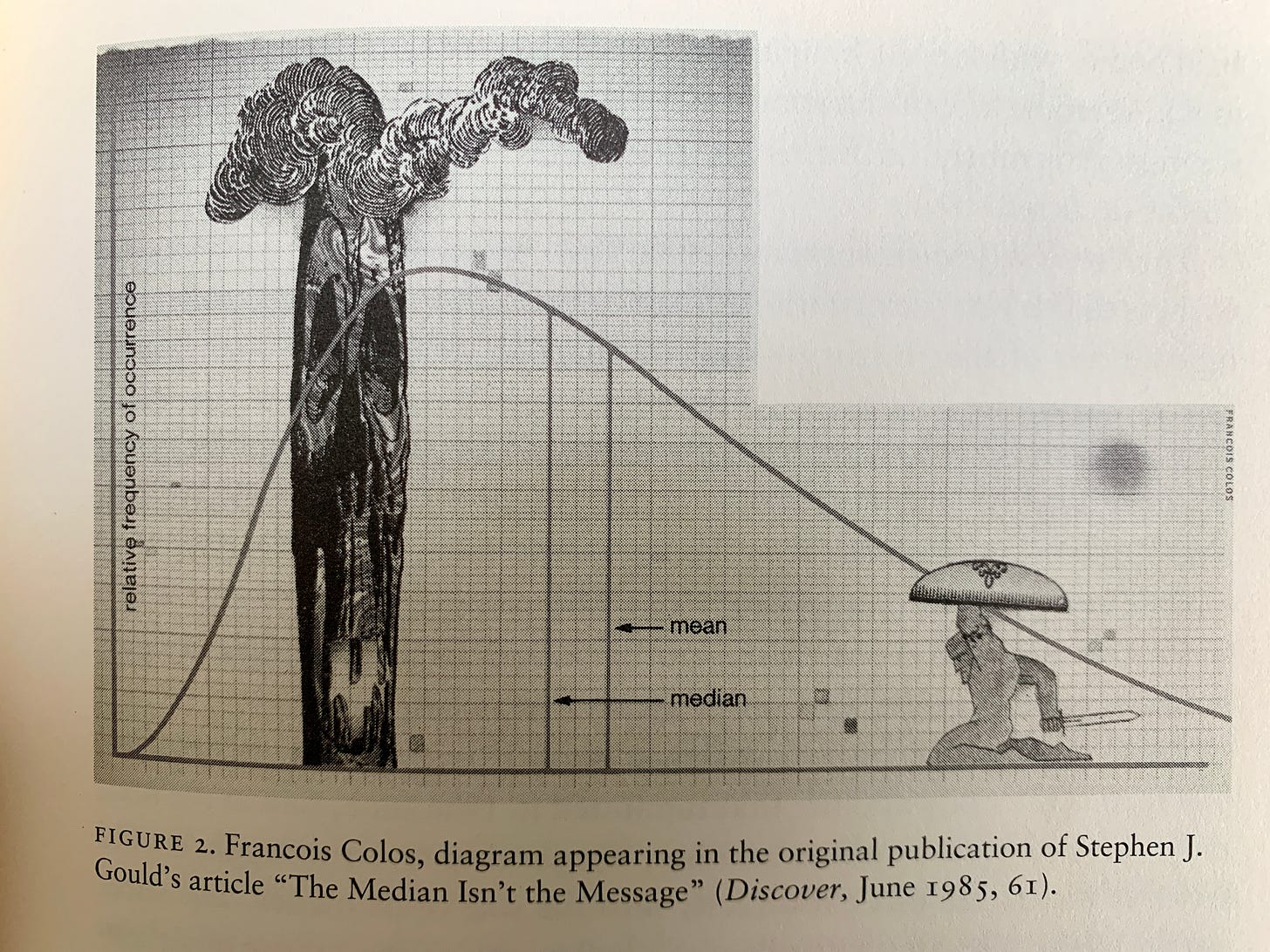

I have two favourite chapters. One, called ‘Living in Prognosis’, grapples with the sticky subject of statistics and life expectancy after a cancer diagnosis. This is a very live and challenging topic for those of us who have had a diagnosis, and as Lochlann Jain points out, there really are only two questions. How many people live, how many people die? And will I be among the former or the latter? This ‘meagre tease toward knowledge’ gives us no definite answer. In the book, a diagram is reproduced which shows a typical bell curve of life expectancy after diagnosis. We all want to be somewhere in the very long tail to the right of the median, but in reality there is very little we can do to ensure we are there rather than in the steep curve on the left.

I have had my own experiences with this. There is a tool produced by the NHS called ‘Predict’. It’s a free online tool for people who have had a breast cancer diagnosis. You can go online and toggle a lot of questions about your diagnosis, your age, what sub type of cancer it was, whether you had any positive nodes, and then you can add all the treatment you have received and start to see its cumulative effect on your chances of survival for 5, 10 and 15 years post-diagnosis (there is no data for more than 15 years). For example, if I had received surgery only, my chances of surviving for 15 years post-diagnosis would be 52%. Because of the extra treatment I have received (chemo, radiotherapy, hormone treatment etc) my chances of surviving to 15 years are 86%. It’s already been over 6 years since my diagnosis, so I’m doing pretty well so far. But what the tool can’t tell me, is whether I personally will be among the 86% who will still be here in 2032, or the 14% who won’t.

Lochlann Jain calls this ‘living in prognosis’ – we may have escaped death for the moment, but its spectre hangs perpetually above us. It alters our relationship with time – with past, present and future. What is our relationship with this number, this percentage prognosis? As Lochlann Jain says, “the number becomes the backdrop against which one can no longer locate the shape of one’s own life”.

And my other favourite chapter is ‘Cancer Butch’, where Lochlann Jain explores the intersection between cancer and gender. This felt so relevant to my own research, and to some of the themes I explored in my MSc dissertation, in which I discussed my complicated relationship with femininity and the drive to reconstruct the self post-cancer. Lochlann Jain is joining the long tradition of feminist academics who use their diagnosis of breast cancer in their critical writing. For example, in her discussion of her mastectomy and refusal to wear prostheses in the 1970s, Audre Lorde critiqued the gendered stigma of breast cancer. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick declared “shit, now I must really be a woman” when she was diagnosed. And Lochlann Jain felt as though breasts had stolen their tomboy youth 25 years previously, and now, newly mastectomised, they take their shirt off in a yoga class to bear witness to ‘carcinogenic culture’ and play with gender norms in a public space.

The book covers a lot of ground, and sometimes lacks focus, but it’s scholarly, angry and elegiac. One of the key questions Lochlann Jain asks is: what constitutes knowledge about cancer? There is a cognitive dissonance:

“The power dynamic resulting from the separation and institutionalisation of knowledge… devalues the knowledge that people with cancer derive from undergoing treatment.”

I think this is a challenge I will encounter as I progress with my PhD. For some people, my lived experience of cancer discredits my scholarship, rendering it too ‘emotional’ and therefore less ‘objective’. For others, it gives me an insider perspective which opens up new possibilities. I choose the latter.